⊹݁˖wₕₒ ₐᵣₑ yₒᵤ?₊⊹

This is the question posed in the 1865 classic, Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll– a unique and fantastical story of a young girl who falls through a rabbit hole into an imaginary world of anthropomorphic creatures. Like most timeless children’s stories, this novel, and its preceding iterations, are steeped with cultural symbols and esoteric meaning. Similar to Odysseus in Homer’s The Odyssey, Alice finds herself on a journey through strange arenas with otherworldly characters; each arena and set of characters acting as both an obstacle and a stepping stone towards a complete understanding, or a completed journey.

Through her plunge into Wonderland, Alice undergoes a ritualistic journey that mirrors many of the worlds ancient shamanic and mythological initiation rites; separation or death from the ordinary world, descent into the underworld, confrontation (with death itself or the shadow), and an ultimate return or rebirth to wholeness. Alice also takes on the process of individuation– a concept of psyche integration later coined in Jungian Psychology.

This analysis will explore some of the ways in which Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland functions as a story of initiatory rite and individuation. I’ll explain some foundational elements of these rites and the process of individuation. I’ll then weave in explanations of symbolic elements as they appear and re-appear throughout the story and how they represent the processes of initiation and individuation.

Want to read or follow on substack? Click here

Elements of Initiation and Individuation

In the 1958 book Rites and Rituals of Initiation, Mircea Eliade lays out the basic patterns of ancient puberty rites, shamanic, cultic, and religious initiations. The introduction covers several basic understandings of these initiation rites,

“Every ritual repetition of the cosmogony is preceded by a symbolic retrogression to Chaos. In order to be created anew, the old world must first be annihilated…..All the rites of rebirth or resurrection, and the symbols that they imply, indicate that the novice has attained to another mode of existence, inaccessible to those who have not undergone the initiatory ordeals, who have not tasted death. We must note this characteristic of the archaic mentality: the belief that a state cannot be changed without first being annihilated—in the present instance, without the child’s dying to childhood.”(Eliade xiii)1

And this is the exact journey, our young novice, Alice takes when she falls down the rabbits hole. She will first retrogress into chaos, and then be called to “taste death”, and “die to childhood” before she can finally reach ‘another level of existence’.

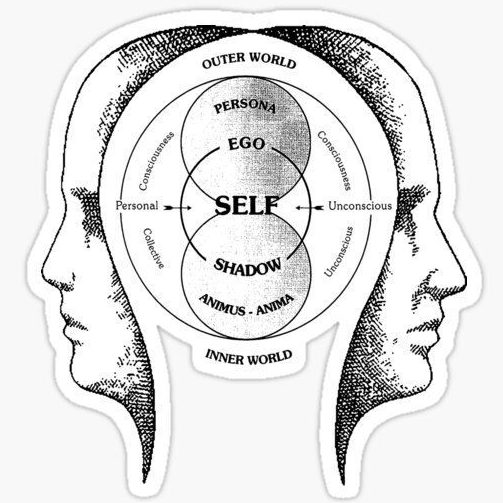

This other ‘level of existence’ is what Carl Jung called individuation. It is the process by which a person retrieves and integrates the unconscious and conscious aspects of the psyche to heal psychological splits or dissonance, ultimately fostering a sense of identity that transcends what is reflected by society. There are four archetypal stages to the process of individuation. I will list them here and later refer to them throughout my analysis.

- 1-Persona: Recognizing the social mask or public face we present to the world and its relation to our true self.

- 2-Shadow: Confronting and integrating the repressed, denied, or hidden aspects of one’s personality that are often considered negative.

- 3-Anima/Animus: For men, confronting the unconscious feminine (anima); for women, confronting the unconscious masculine (animus) to achieve balance.

- 4-Self: The goal is to reach the Self, which represents the unified totality of the personality, encompassing both the conscious and unconscious.

Alice’s plunge down the rabbit hole begins the descent to chaos and confusion. As the novice in this initiation, Alice possesses two traits worth noting: a boundless curiosity and a deep respect for order. These qualities are not opposites but complements–curiosity drives the questioning that opens doors to the unknown, while order structures the chaos revealed. In this way, Alice’s own curiosity both begins her journey into the unknown and eventually reconciles her home to the known, or to the Self. We will cover these character traits further in the Symbolism of The Queen of Hearts, but it’s important to note this dichotomy in Alice’s values as the foundational element of our story because it brings us to the central question of Alice’s journey in Wonderland: “Who are you?”

The Underground Forest; Symbolic Death, Retrogression to Chaos, and Resurrection

1. First Step of Initiation: Symbolic Death

Alice’s story begins in the most crucial state of boredom.

“She was considering in her own mind (as well as she could, for the hot day made her feel very sleepy and stupid), whether the pleasure of making a daisy-chain would be worth the trouble of getting up and picking the daisies,”.(Carroll ch.1)2

In her languid, sleep-like state, Alice hardly contains the ability to consider her own desires, let alone carry them out. We can call this a psychic slumber; a state in which one is “sleepwalking” through life, carrying out the duties of their day-to-day, yet blind to their own nature and choices; Like a passenger blind to who’s driving their vehicle. This loss of faculty is the first step of a symbolic death. One who loses their ability to consider the drivers of their inner world remains stuck in this languid, zombified shape, stuck in the sleepwalking until something catches their eye and awakens them from the sleepwalking. For Alice, that will be The White Rabbit.

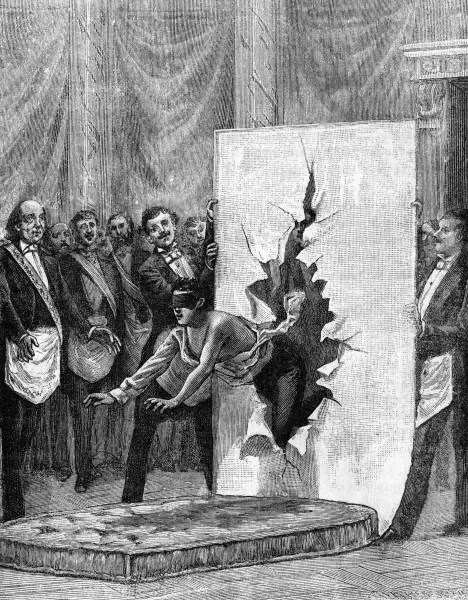

Another important element of Alice’s initiation is her separation from the Mother, or the protective figure. Across cultures, the first step of initiation is isolation. The Murring, for example, cover mothers with blankets and sit their novice boys in front of them. At a particular moment, the novices are seized and taken away by the men of the tribe. Another common symbol in the isolation stage is a tree, hedge, or other plant covering. The initiation ceremonies are called Kuringal, “belonging to the bush.” The scenario is similar, according to Howitt, the women are covered with branches and blankets, the novices are seized by their guardians and carried off to the forest, and there daubed with red ocher.3

Alice’s chase after The White Rabbit, leading her away from the safety of her older sister, is her isolation stage. The chase leads Alice to the field where she watches the rabbit disappear underneath a hedge. Fatefully, she follows and falls, well, slowly descends, down the rabbit hole. And just like the Wiradjuri, Alice “belongs to the bush”, thus begins her plunge into Wonderland, a.k.a the underworld

Symbol: The Hedge and Rabbit Hole

If we want to think about what a bush or hedge covering represents, we can look to the book of Exodus, wherein the divine covers itself in a burning bush to protect Man from its image. The Lord calls out and speaks to Moses from the bush, but does not reveal Himself beyond the bush(Exodus 3:1-6). Nature acts as a mediator between God and man. Canadian iconographer and symbolist Jonathan Pageau often explains that symbols are the means by which the hierarchical nature of existence is apprehended and meaning from this patterned reality is drawn. Because the earth was created before man, it makes sense that it would be closer to God in terms of spiritual hierarchy and that God would need to communicate, or cover Himself, to man through this lower hierarchical level. In this way, Alice’s plunge into a rabbit hole hidden by a hedge is meant to symbolize a plunge into the divine; a move beyond the mediator.

Symbol: The White Rabbit

When Alice first notices the rabbit, she barely reacts. A talking rabbit passes by, and she lets it go. Only when it pulls a pocket watch from its waistcoat does her curiosity ignite. Carroll writes,

“There was nothing so VERY remarkable in that; nor did Alice think it so VERY much out of the way to hear the Rabbit say to itself, ‘Oh dear! Oh dear! I shall be late!’ … but when the Rabbit actually TOOK A WATCH OUT OF ITS WAISTCOAT-POCKET, and looked at it, and then hurried on, Alice started to her feet, for it flashed across her mind that she had never before seen a rabbit with either a waistcoat-pocket, or a watch to take out of it, and burning with curiosity, she ran across the field after it,”(Carroll ch.1)

The White Rabbit acts as Alice’s inner messenger. Like the fleet-footed god Mercury, the White Rabbit is all motion and urgency, a herald of things to come. Just before Alice is swept away in her sea of tears, she sees him again, hurrying down the hallway: “Oh! the Duchess, the Duchess! Oh! won’t she be savage if I’ve kept her waiting!” (Ch. 1). In this moment, we receive a glimpse of the messengers destination, the object of the journey.

The rabbit’s pocket watch and his restless haste open the door to our next symbol: Time.

2. Second Step of Initiation: Retrogression to Chaos

Symbol: The Pocket-Watch and Time

As Alice is making her descent to Wonderland, there are a few key images and symbols that help to cue us into some of the more layered symbols we’ll see later on. The first of which is the symbol of Time. The pocketwatch of the rabbit is what caught Alice’s eye and led her to follow. Is Alice chasing the rabbit or chasing time?

Time is an essential aspect of reality and worldly order. It’s a law we cannot help but live and organize by. In the process of retrogression into chaos, reality before order, one must be unchained by the laws of reality that exist. Eliade discusses the element of Time as it relates to aboriginal initiations,

“This is why the initiation ceremonies are so important in the lives of the aborigines; by performing them, they reintegrate the sacred Time of the beginning of things, they commune with the presence of Baiamai (Aboriginal Sky Father and God of Creation) and the other mythical Beings, and, finally, they regenerate the world, for the world is renewed by the reproduction of its exemplary model”(Eliade p.6)

Eliade says that to the aborigines, the reproduction of divine creation aids in the restoration of the world. If Time is a crucial part of the organization of creation, then the novice must experience existence outside of that organization. As Alice falls down the hole we see how time begins to warp, “she fell very slowly, for she had plenty of time as she went down to look about her and to wonder what was going to happen next.”(Carroll ch.1). This warping of Time is a breakdown of Alice’s reality

The symbol of Time revisits as we meet the Mad Hatter. He shares a discussion with Alice about Time, only, Time is not a concept to the Hatter, but a real character. He suggests that Alice befriend Time or else Time will not obey, or, be good to her. According to the Hatter himself, he once “killed Time”. As a result, the Hatter is damned to perpetual tea time.

“Well, I’d hardly finished the first verse..when the Queen jumped up and bawled out, “He’s murdering the time! Off with his head!”‘

…And ever since that, he won’t do a thing I ask! It’s always six o’clock now.’.. ‘it’s always tea-time, and we’ve no time to wash the things between whiles.’ (Carroll ch.7)

The Hatter offers us the complete dissolution of time itself. Alice has no need for the time or any clocks where it’s 6pm forever!

Symbol: The Door and Key

After her fall, Alice lands in a hallway full of locked doors and a single key. She has her first trouble, the key doesn’t fit any of the doors. After her second time around the room she finds a curtain that wasn’t there before, and behind it a small door. To her avail, the lock of the small door matches the key!

Doors are thresholds. Such a simple symbol creates a vast web of meaning, but what’s more meaningful than the door itself is how she happened upon it. Alice was placed in a room with an endless number of doors. Her curiosity circles her around the room, attempting to open each one. Only after she’s attempted every locked door does the door finally appear. Sometimes when we’re looking for a threshold, for a new path or answer, one must first wander awhile. With our aim held firmly, the door will eventually appear, maybe cloaked, but it will appear. Once Alice found the door, she faced a new issue: she wasn’t the right size to fit through! There’s something about Alice that isn’t able to pass through the door, indicating a change must occur. Despite the door being open and within reach, she will need to undergo a transfiguration to pass through. This need for change brings us to the symbol of elixirs and other consumables.

Symbol: Elixirs and Consumables

Throughout the story, Alice is given unlabeled consumables ranging from drinks to cakes and mushrooms. Consumables are another simple symbol capable of many meanings, but these consumables only offer Alice the ability to change in physical size. In the hallway of doors, she goes back and forth between the consumables rapidly changing her height. Testing and consuming the size-changing elixirs acts as a representation of Alice figuring out how to (or how not to) grow up. Consumables in stories remind us of that which we take into ourselves. It can represent things we digest or things that become a part of us. Alice struggles to determine which aspects of herself to integrate into adulthood and which to leave behind in childhood. In her anguish, she questions if she’s been changed overnight,

“Let me think: was I the same when I got up this morning? I almost think I can remember feeling a little different. But if I’m not the same, the next question is, Who in the world am I? Ah, THAT’S the great puzzle!”(Carroll ch.2)

Alice declares her mission and prepares to embark on her journey of self actualization. Soon enough, Alice finds herself swimming in an ocean of her own tears. Thus begins the retrogression into chaos.

Symbol: Tears

Nearly every creation story begins with great primordial waters; the Hebrew Tehom, Egyptian Nun, Sumerian Namma, and of course, the Greek Chaos! These vast formless seas have a name in every culture, and in Wonderland, they take the form of Alice’s tears.

In Chapter 14 of Women Who Run With the Wolves, “La Selva Subterránea: Initiation into the Underground Forest,” Clarissa Pinkola Estés reflects on the strange, transformative nature of tears. It’s impossible for me not to think of Alice–adrift and overwhelmed in her ocean of sorrow—as if Estés were somehow writing about her all along.

“…tears make us conscious. There is no chance to go back to sleep when one is weeping…Sometimes a woman says, ‘I am sick of crying, I am tired of it, I want it to stop.’ But it is her soul that is making tears, and they are her protection…Some women marvel at the water their bodies can produce when they weep. This will not last forever, only till the soul is done with its wise expression.”4(Estés 437)

In this light, Alice’s tears are not just a symptom of distress; they are the deluge that dissolves her former world. Like the primordial waters of myth, they are both destructive and generative, sweeping away the former realities so that the new can appear.

3. Third Step of Initiation: Resurrection

Symbol: Caterpillar

The Caterpillar is one of the story’s more overt symbols– a creature poised between forms, embodying metamorphosis and self-actualization. The caterpillar undergoes a kind of miniature death, sealing itself in a cocoon before re-emerging unrecognizable. In this liminal space, the once earthbound belly crawler transforms into a creature of flight. Here, metamorphosis is not just about change, but about liberation towards destiny. This journey of metamorphosis is framed by the Caterpillar repeating Alice’s enigmatic question, breathing coils of smoke into the air: “Who are you?”

the shadow

Symbol: Duchess and Queen

The White Rabbit ultimately leads Alice to two powerful female figures: the Duchess and the Queen of Hearts. Together, they reflect Alice’s split nature—her Persona and her Shadow. We learn about Alice’s dual nature very early in the story:

“…sometimes she scolded herself so severely as to bring tears into her eyes; and once she remembered trying to box her own ears for having cheated herself in a game of croquet she was playing against herself, for this curious child was very fond of pretending to be two people. ‘But it’s no use now,’ thought poor Alice, ‘to pretend to be two people! Why, there’s hardly enough of me left to make ONE respectable person!”(Carroll ch.1)

While one side of Alice is imaginative and childlike; the other is self-critical, bound to reason and propriety. Her Persona is rooted in good manners and education, but her Shadow emerges as a sharp, impatient voice, intolerant of Wonderland’s lack of “sense.” The Queen of Hearts personifies this side—ruthless, authoritarian, and obsessed with order.

The Queen of Hearts is a ruthless, unjust judge. Her subjects: a deck of cards. The deck of cards represents a court of law, a symbol of order, and social class. A court, much like a game of cards, requires rules and order to be upheld. But in the court of The Queen of Hearts, it is not fairness or justice that is upheld, but unjustice.

Alice first finds the cards painting white roses with red paint and bickering in the Queen’s garden. One card says to another, “Well, of all the unjust things—”(Carroll ch.7). This emphasizes the value of unjustice in The Queen’s court. Later in the Disney film adaptation, we receive a song titled “Happy Unbirthday”, further emphasizing the “un-ness” of Wonderland.

It’s important to emphasize that Wonderland is not the opposite of reality, but the undoing of reality. The undoing of our reality, of ourselves, is the process of Individuation; a dismantling of the constructed self to reveal the true Self beneath.

If life is moving in a forward spiraling motion, going to wonderland is the unspiraling.

Symbol: Beheading

The Queen’s infamous command isn’t a whimsical quip, it’s a psychic dismemberment. The head represents one’s dominion; it is the source of our knowledge and the seat of our understanding. When the head is removed, one becomes like a zombie, a body without a conscious controller, a shell. Dismemberment in fairytales signals a loss of vital faculties. If dismembered, it is crucial to retrieve the dismembered parts and reclaim personal authority. This reclamation awakens the psychic slumber. Estés shares a folk story called The Handless Maiden in chapter 14 of Women Who Run With The Wolves. In her dissection of the folktale, Estés discusses the relationship between psychic slumber and dismemberment,

“That female psychic slumber is a state approximating somnambulism. During it, we walk, we talk, yet we are asleep.” ( Estés p.427)

The Queen prefers dismembered subjects because they’re easily enslaved, lack the ability to self-actualize, to desire, or to develop. “The Queen had only one way of settling all difficulties, great or small. ‘Off with his head!’ she said, without even looking round.”(Carroll ch.7).

The Queen of Hearts doesn’t deliberate, only punishes. In meeting with and challenging the Queen of Hearts, Alice is facing her shadow. She begins to unspiral her capability of harsh judgment, self-punishing tendencies, and obsession with order.

This shadow emerges again when Alice and the Duchess reunite on the Queen’s croquet grounds. Alice is happy to see the Duchess this time and remarks on her change of temper. Alice decides that the Duchess is no longer under the irritant of black pepper and she declares a new rule in her imaginary dominion:

“When I’M a Duchess,’ she said to herself,… ‘I won’t have any pepper in my kitchen AT ALL…—Maybe it’s always pepper that makes people hot-tempered,’ she went on, very much pleased at having found out a new kind of rule…“(Carroll ch.9)

Here, met by The Duchess, Alice continues to reveal her shadow nature: Obsession with order. Alice, like the Queen of Hearts, prefers to impose order rather than accept the occasional peppery attitude of her subjects. While Alice’s motives might seem good-natured, she is similarly beheading her own subjects. Rather than a deck of cards, Alice’s “subjects” are her own faculties. When she makes a declaration about how she’ll rule her kingdom, we must remember that her kingdom is her own Psyche. When Alice beheads or imprisons her subjects, she is actually beheading her own abilities, desires, and emotional whims.

the animus

Symbol: Mad Hatter

According to Jung, the Animus is “a psychopomp, a mediator between the conscious and the unconscious and a personification of the latter” (Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self). The Mad Hatter, whimsical yet erratic, can be read as Alice’s wounded Animus. A hatter protects and adorns the head. The head is the symbolic “crown,” the seat of thought, and the channel between consciousness and the divine. In this way, he stands in stark contrast to the Queen, who seeks to sever heads entirely. Where the Queen’s impulse is to destroy, the Hatter’s symbolic role is to safeguard Alice’s whimsy, her childlike spirit, and her link to higher awareness.

In the real world, hatters were known to go “mad” from their exposure to mercury in the hat-making process. Similarly, when the Animus is injured or left in the unintegrated, it can manifest “mad” traits such as rigidity, aggression, and stubbornness.

‘I don’t think—’

‘Then you shouldn’t talk,’ said the Hatter.”

This blunt dismissal is more than Alice can bear, and she walks away in disgust. The Hatter, meant to protect and guide, wounds her instead. Although wounded, another male figure in Wonderland reveals that the Animus is not entirely lost.

Symbol: King

The Red Queen’s consort, the King of Hearts, holds far less visible power than his wife. This imbalance reflects how the Shadow can overpower the logical and protective elements of the psyche. But during the Queen’s croquet game, after she orders nearly everyone’s execution, the King quietly asserts himself:

“As they walked off together, Alice heard the King say in a low voice, to the company generally, ‘You are all pardoned.’ ‘Come, THAT’S a good thing!’ she said to herself…” (Carroll ch.8)

The Animus’ duty is to provide rationality to the female psyche. The King’s understated act, though private, is witnessed and appreciated by Alice. In recognizing and valuing his quiet justice, Alice moves towards a state of inner balance and is nearing the reclamation of her psyche.

the self

4.Integration and Return to Reality

Our final destination in Wonderland is the Queen’s court. At first, Alice greets the courtroom with excitement. She takes note of all the things she’s familiar with, including the judge and jury box. But as the trial lurches forward in all its absurdity, something remarkable happens: Alice begins to grow again. This time, she consumes no magical cake or elixir; her change is self-generated. This moment signals that something inside Alice has matured and grown.

As the trial draws to a close, the King demands court herald, the White Rabbit, to announce a final witness. And of course, it’s Alice. The very messenger who once lured her into the underworld of Wonderland now completes his task, delivering her into the hands of her accusers—into the symbolic grasp of death itself.

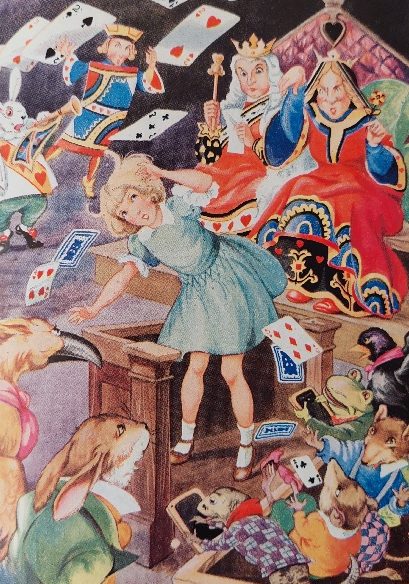

True to her unjust nature, the Queen insists that the jury deliver their sentence before hearing the verdict. This gross delineation from proper order becomes Alice’s final straw in Wonderland. Alice takes stand against the Queen and openly condemns her nonsense. In response, the Queen orders for Alice’s beheading. But now, Alice stands in her full stature, both literally and psychically:

“Who cares for you?’ said Alice, (she had grown to her full size by this time.) ‘You’re nothing but a pack of cards!”

In rejecting the Queen’s authority, Alice dissolves her own Shadow and reclaims the totality of her Psyche. She has faced the final step of initiation: confrontation with death. And, she has concluded her process of individuation: meeting every part of herself, integrating them, and emerging whole.

🃜🃚🃖Conclusion 🃁🂭🂺

After denying the Queen, the pack of cards flies up in a flurry around her and she awakes in the lap of her older sister. Carroll notes that Alice has returned to her full size, symbolizing an end to her journey. She’s met all aspects of herself; chaotic and ordered, sorrowful and joyful, drowsy and alert, kind and unkind, just and unjust. Having faced these polarities in the underworld, she can now return to reality and continue the process of maturation. As in every true initiation rite, the novice brushes against death and emerges back into the living world transformed.

The story closes from the vantage point of Alice’s older sister, who sits quietly, recalling her own adolescent wanderings through Wonderland—proof that she, too, has traversed the initiatory underworld. She envisions Alice as a grown woman:

“Lastly, she pictured to herself how this same little sister of hers would, in the after-time, be herself a grown woman; and how she would keep, through all her riper years, the simple and loving heart of her childhood…”.

From this perspective, we sense a fulfilled cycle. We trust that Alice will mature in the same way that her sister has, carrying forward the lessons of her journey.

By ending the story in the sister’s eyes, Carroll offers a true “full circle moment” akin to Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey. Campbell defines the Hero’s Journey as a cyclical narrative in which the hero returns to the ordinary world, transformed by their experiences. The “full circle” signifies the completion of a quest, returning to reality with the lessons, or “elixir,” to enrich their original world.

In Alice’s case, she descends into the underworld to reclaim the totality of her Psyche. Without recovering her childlike nature and sense of wonder, she would have continued to age in a state of psychic decapitation—a life ruled by her Shadow, by the Queen of Hearts: dismembered, disconnected, and drifting in a kind of spiritual slumber.

Personal Reflection

This story has been with me for as long as I can remember. I’ve always felt an intimate, almost uncanny connection to its characters. My dream world, even as a child, carried an eerie depth. Looking back, I now recognize many of my recurring childhood dreams as initiatory psychic journeys. In waking life, I was confronted with dark forces early on; in the dreamworld, I was prepared for them, taught to recognize, face, and speak to them. Like Alice, I let my curiosity guide me through the dark forest.

What’s remarkable is how the story has aged alongside me. I’ve long adored the 1951 Disney adaptation for its musical whimsy and faithfulness to Carroll’s text. Tim Burton’s reimaginings of Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass also hold a special place in my heart and would deserve full dissections of their own for their depths. I remember fondly, my eighth birthday, celebrated with a premiere viewing of Burton’s Alice in Wonderland. In recent years, I’ve also fallen in love with the Japanese thriller series Alice in Borderland, which carries many symbolic echoes to the childhood classic.

Wonderland continues to weave itself into the fabric of my life. These days I find myself relating to Alice’s older sister. Like her, I look forward to sharing this magical world with the people and children I love, and to watching them grow with the same sense of wonder that has accompanied me all these years.

If you’ve read this far, thank you. I hope you enjoyed.

Till next time, with love, Chloeandclover ☘︎ ݁˖⋆xoxo

♤♡♧♢ Other notable symbols♤♡♧♢

Cheshire Cat and Dinah Cat: God, higher consciousness, spiritual guardian, only character she feels safe communing with, always reaffirming her, smiling down

Painting White Flowers Red: Painting purity with blood, the onset of menses

Caucus Race: Absurdity, senselessness, political folly, cycles/Samsara

Dormouse and March Hare: Psychic slumber, foil characters; both enter strange states for a season, the March hare goes mad whereas a dormouse hibernates.

- Eliade, Mircea, and Williard R. Trask. Rites and Symbols of Initiation. Harper Colophon Books, New York, 1958. Digitally republished by Digital Library of India via Internet Archive, item dli.ernet.6032, accessed August 7, 2025. ↩︎

- Carroll, Lewis. Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Apple Books Classics edition, released November 25, 1865 [e-book], Public Domain (Apple Books), accessed August 7, 2025. ↩︎

- Howitt, Alfred William. The Native Tribes of South-East Australia. London: Macmillan, 1904. Chapter IX (pp. 509), accessed [digital edition], Internet Archive, item dli.ernet.6032, accessed August 7, 2025. ↩︎

- Estés, Clarissa Pinkola. Women Who Run with the Wolves: Myths and Stories of the Wild Woman Archetype. 1st Ballantine Books trade paperback ed. New York: Ballantine Books, 1995. ↩︎

2 responses to “The Symbolic World of Wonderland: Alice’s Journey of Initiation and Individuation – An Esoteric Analysis of Lewis Carroll’s “Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland””

Thank you for sharing this with us! This was a very emotional read for me as I’ve seen so many parallels in my own life with the concepts you’ve unraveled and explored, but also while reading I felt a few full circle moments of my own come through. Anyone on “the path” (iykyk) would benefit from reading this- especially the section about the Queen of Hearts in my opinion.

Also, it’s the careful and loving creation and execution of slow form content like this that just gives me LIFE. So thank you again. Excited for your next post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the kind and well thought out response and review. This story is an emotional one for me every time I come back to it. I’m so glad to have translated and evoked similar feelings. And to your sentiment about slow form content, I couldn’t agree more! Again, thank you so so much, I’m so grateful to share this with you. Cheers to falling down rabbit holes!

LikeLike